Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson,

with whom Justices Kagan and Sotomayor join dissenting

Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College Nos. 20-1199 and 21-707 Decided June 29, 2023

In SFFA v. Harvard and UNC the Supreme Court took a blunt hammer to the principles which have governed university treatment of applicants’ race since Bakke v. Regents in 1978. Already on the way to abandoning Brown v. Board’s integration mandate in all but the narrowest circumstances Allen Bakke successfully challenged the University of California Davis Medical School in what was then called a “reverse discrimination” case. UC Davis’s affirmative action plan survived but just barely.

In his 1074 Bakke concurring opinion Justice Lewis Powell said that diversity of student body could be seen as a a compelling state interest. In a sentence that would change the language and the approach of competitive colleges and universities for almost fifty years Powell - for the court found that “the goal of achieving a diverse student body is sufficiently compelling to justify consideration of race in admissions decisions under some circumstances.” Every admissions officer and committee since has explored the meaning of “”a diverse student body”.

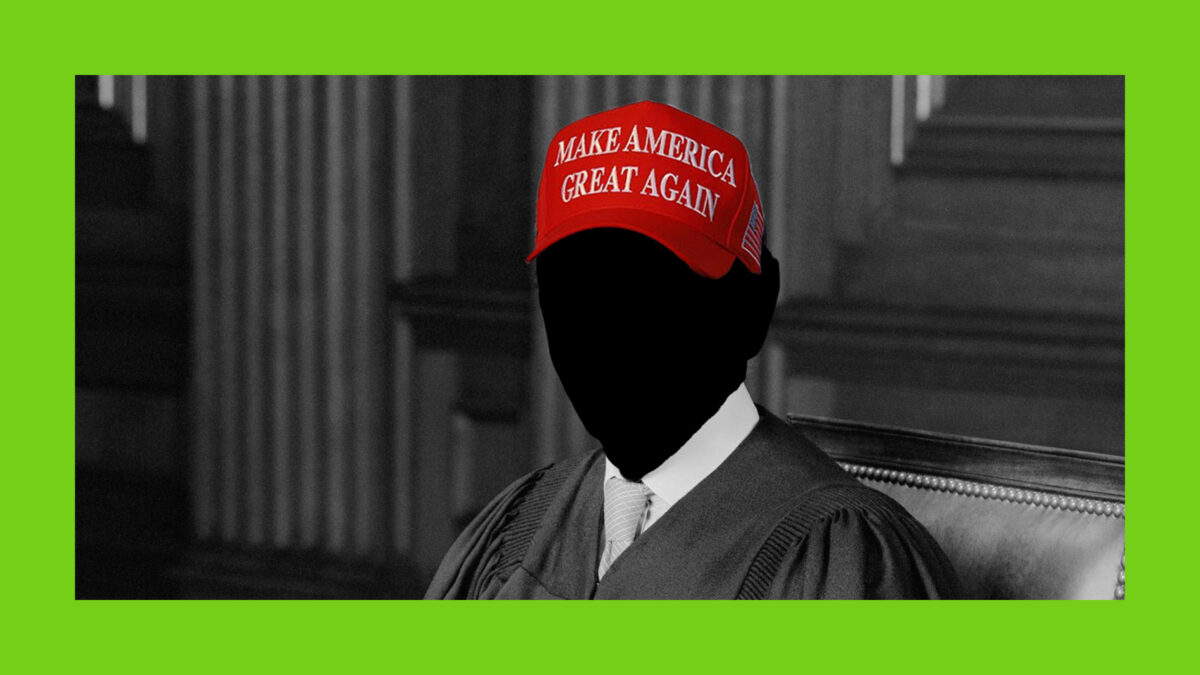

Ketanji Brown Jackson - recently appointed and the first African American woman to serve on the high court was blunt. She opened with this:

Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations.

Such references to the consequences of past discrimination have been out of favor since 1988 when in Croson v. City of Richmond Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that a “generalized” history of discrimination did not justify the City’s remedial quota system. In the landmark Parents Involved v. Seattle [2008] The Chief Justice famously paraphrased another judge to say that “the way to stop discrimination by race is to stop discriminating by race”. There the plurality renounced even voluntary public school integration plans. Stephen Breyer, in his dissent, defined such plans as “race-conscious desegregation measures that the Constitution permitted, but did not require ”.

Brown Jackson continued that argument by Justice Breyer for whom she had clerked. She rebutted the view that “it is unfair” for a college to to “consider race as one factor”in admissions. She concluded:

Given the lengthy history of state-sponsored race-based preferences in America, to say that anyone is now victimized if a college considers whether that legacy of discrimination has unequally advantaged its applicants fails to acknowledge the well-documented “intergenerational transmission of inequality”that still plagues our citizenry. It is that inequality that admissions programs such as UNC’s help to address, to the benefit of us all. Because the majority’s judgment stunts that progress without any basis in law, history, logic, or justice, I dissent.

We can see the legacy of discrimination in Maureen O’Connell’s Undoing the Knots which shows the long history of housing discrimination in Philadelphia, in Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, and in recent panelist Kevin Boyle’s National Book Award winner Arc of Justice which tells a story of racial discrimination in housing in Detroit in the 1920s.

But now - as we have learned of the broader and deeper history from Fr. Kellerman, What is to be done? As a Catholic institution which served immigrants who themselves were often anti- Black do we have a special obligation to made amends