In the late 1850s, a slave named Ned invented a “double plow and scraper,” which enabled a farmer to plow and scrape both sides of a row of cotton simultaneously, among other things, depending on the configuration of its plow and scraper blades.68 Ned belonged to Oscar J.E. Stuart, a lawyer and planter from Holmesville, Mississippi, and Stuart hoped to patent Ned’s promising invention.

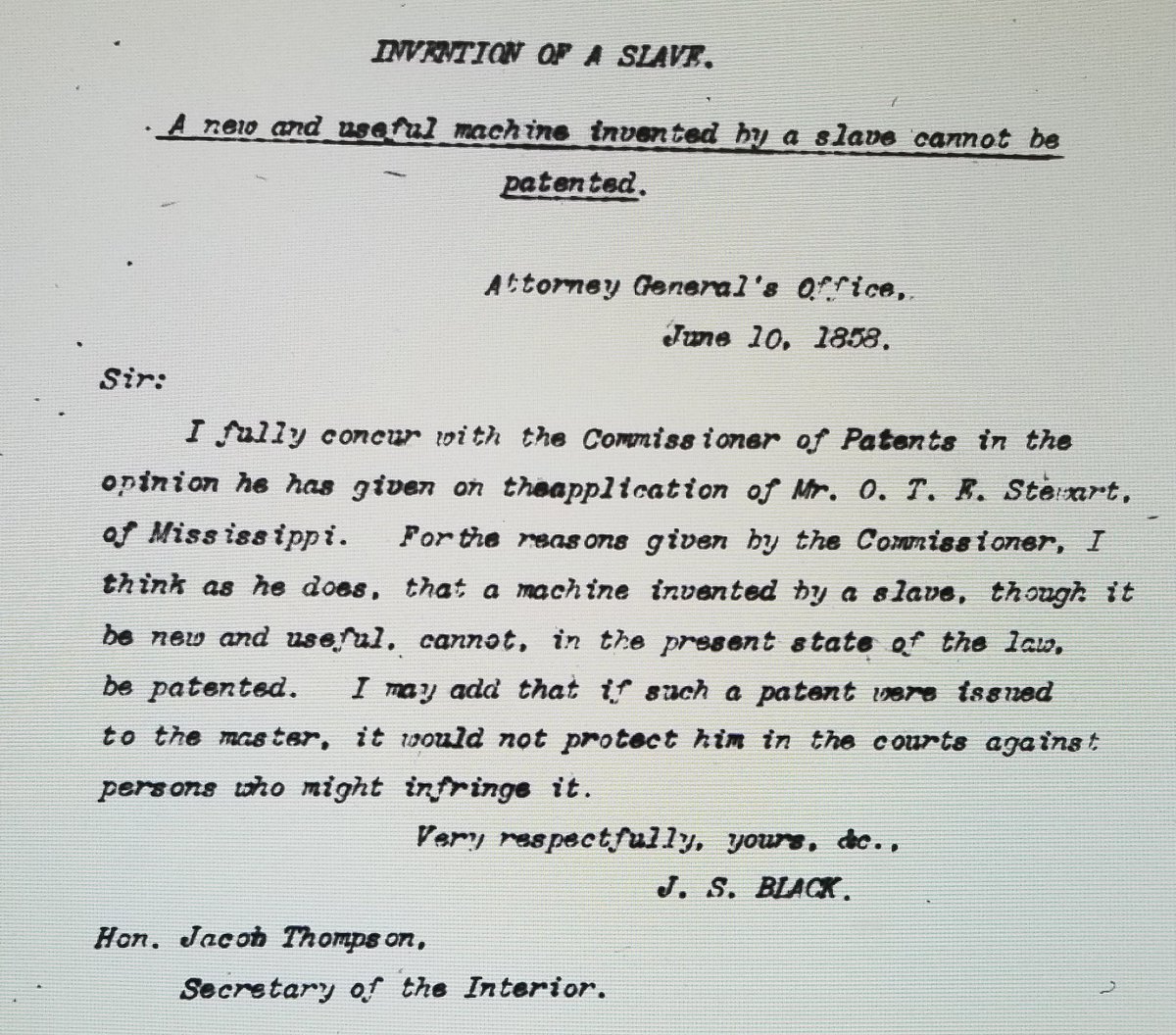

On June 10, 1858, the Attorney General issued an opinion titled Invention of a Slave, concluding that a slave owner could not patent a machine invented by his slave, because neither the slave owner nor his slave could take the required patent oath. The slave owner could not swear to be the inventor, and the slave could not take an oath at all.The Patent Office denied at least two patent applications filed by slave owners, one of which was filed by Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi,who later became the President of the Confederate States of America. But it also denied at least one patent application filed by a free African-American inventor, because African-Americans could not be citizens of the United States under Dred Scott.Brian L. Frye, 68 Syracuse Law Review 181 (2018)

RACE AND SELECTIVE LEGAL MEMORY: REFLECTIONS ON INVENTION OF A SLAVE - Columbia Law Review

by Kara Swanson (2020)

Even as a small-scale story of slavery in the antebellum United States, Invention of a Slave provides a poignant example of the contradictions between humanity and property that challenged and distorted American law in a slave society. It forces us to acknowledge that the ideology of slavery reached into the technical bureaucracy of the patent office, an area of law and of the administrative state frequently considered outside politics. The dry lines of the opinion expose the breathtaking claim by an enslaver to the mental labor of another person—an ultimate claim of whiteness as intellectual property—and another frontier in the “myriad and nefarious uses of slave property.” These features make Invention of a Slave a story worth remembering.

***

What were the stakes that drove African American activists and leaders to tell and retell the story of the enslaved inventor and his exclusion from the patent system? I argue that this memory work was performed in support of fights for the “rights of belonging,” the various civil rights that signal and accompany inclusion.

Between the formal lines of the opinion, these activists read an unintended message that patents could be political tools used to oppose anti-black racism and racist laws. They mobilized patents as government certifications that their recipients had a prized mental ability, inventiveness, in order to undercut the logic of racism in its shifting guises, including scientific racism, white supremacy, and the pernicious bigotry of low expectations. This labor resulted in publications that remained on the other side of a color line, excluded from the acknowledged repositories of legal memory.

This exclusion has carried costs, as we in law have failed to appreciate and participate in what was always in part a legal effort, even though it occurred outside formal legal publications. These storytellers, by telling one of law’s stories, were seeking legal change. Our legal erasure of both the opinion and storytellers has allowed us to encounter a well-remembered story as “forgotten” and remain blind to its relevance.

No comments:

Post a Comment