| James Obergefell and Chris Geidner |

The post-Obergefell same-sex marriage Statement Calling for "Constitutional Resistance" by uber conservative Robert George has found resonance with allies like Justice Antonin Scalia. Some rallied to County Clerk Kim Davis in Kentucky - and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has suggested that county clerks may be entitled to exemption from following the Supreme Court's dictates.

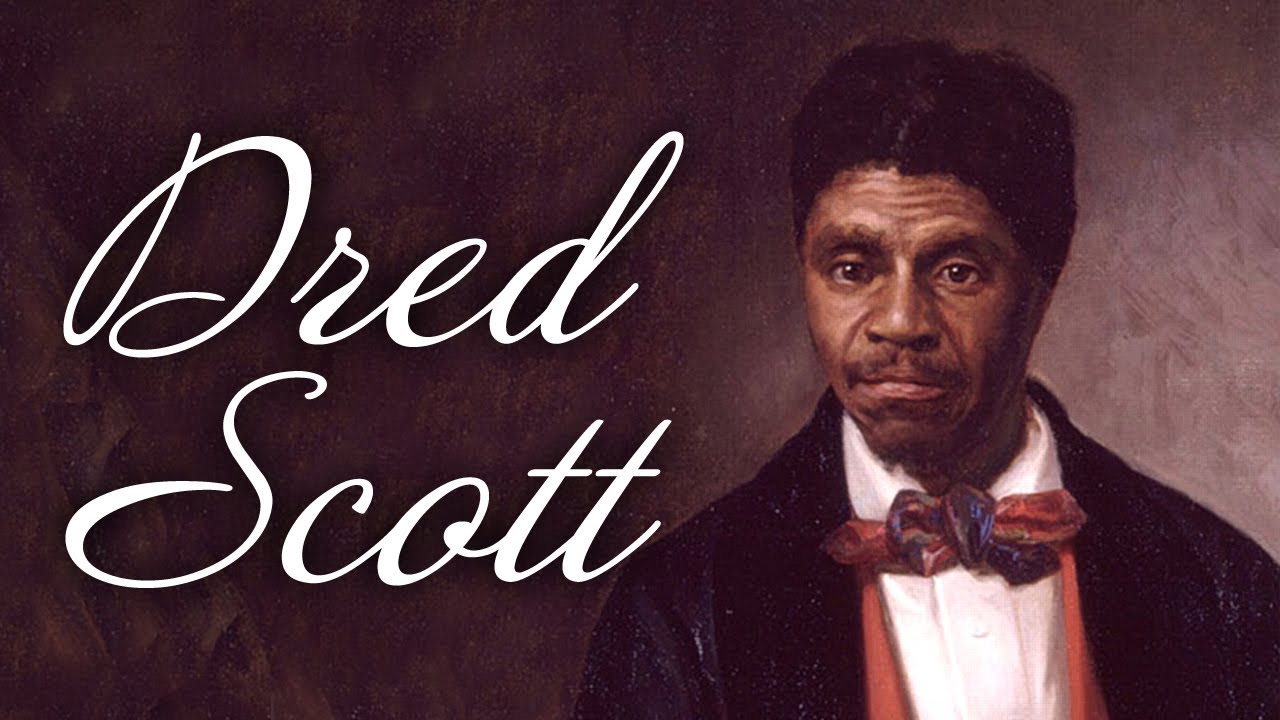

Former Scalia clerk and Catholic conservative Kevin Walsh at University of Richmond has acted to support his former mentor by explaining that there is no defiance of law in comparing Obergefell to Dred Scott v. Sanford, that the judiciary is supreme only in its own "department", leaving other departments of government free to pursue their own visions of the Constitution. Judicial supremacy - the product of Marbury v. Madison as now understood - has long invited celebration and vilification, depending usually on whose oxen have been gored.

Prof. Howard Wasserman who is not in the same ideological camp has embraced the "departmentalism" notion. In my view signing on to Walsh's label is hazardous. Of course every branch of the government participates in the development of thinking within or about the framework of the constitution. But in practice the current slogan as inspired by George - who denounces Obergefell as illegitimate as was Dred Scott - is a dangerous development.

Those like Chief Justice John Roberts who in dissent denounced Obergefell ("By deciding this question under the Constitution, the Court removes it from the realm of democratic decision") are playing a risky game. The majority decision giving the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush is subject to the same attack as Roberts makes now. Judicial humility did not prevent Roberts from striking Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act; nor from striking the voluntary racial integration plans of the Seattle public schools. Such decisions cannot be resolved by neutral principles. They require prudential judgments; judiciousness rather than "constitutional resistance" is the better watchword.

In Texas an ethics complaint has been filed against the Attorney General. The tactical wisdom of that is dubious. We can see a judicious approach in the recent order of federal Judge David Bunning in Kentucky. He has declared himself satisfied that his order to provide marriage licenses to all qualified applicants has been met by the office of the county clerk. He did not require that Kim Davis's or even the county's name be on it. Davis substituted "issued by federal court order" for the name of the county. Bunning, finding that the validity of the licenses is not in doubt, chose deference rather than further confrontation. Substance over form. Discretion can be valor. - gwc

PrawfsBlawg: Judicial supremacy and professional responsibility

by Howard Wasserman

The ethics complaint filed against Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton last summer will proceed to a State Bar investigation. (H/T: Josh Blackman) The complaint stems from a letter Paxton sent to county clerks in the wake of Obergefell, suggesting clerks and justices of the peace may have a religious exemption from issuing licenses or performing marriages to same-sex couples and that they may be able to assert those requests for exemption.

One of the challenges to the model of departmentalism I have been advocating (what Richmond's Kevin Walsh calls "judicial departmentalism") is the many doctrines that reinforce judicial supremacy. State bar regulations appear to be one of them, if this complaint against Paxton goes anywhere. The explicit problem, according to the complaint, is that Paxton ignored Obergefell and the (supposed) supremacy of SCOTUS's interpretation of the Constitution; his legal advice thereby ran afoul of several rules of professional responsibility. In fact, Paxton expressly acknowledged that any clerk or JOP who did this would almost certainly be sued, held liable in light of SCOTUS (and 5th Circuit) precedent, and subject to an injunction that would bind them. He simply recognized the need for that additional step. But that is not good enough; because it is "emphatically the province and duty," etc., an attorney, even one for the State, cannot give advice contradicting such judicial declarations. If this is what the regulations mean, they leave no room for departmentalism or for independent constitutional judgment in non-judicial actors; they instantiate judicial supremacy as the sole understanding for all attorneys, public or private.

On one hand, that could be permissible and appropriate. If a state legislature wants to establish judicial supremacy as the guiding principle for its attorneys, (so that, for example, the obligation to not advise a client to disobey a legal obligation includes obligations established in judicial decisions to which the client is not a party), it can do so. On the other hand, the automatic acceptance or presumption of judicial supremacy into the rule, without more, seems difficult to square. And somewhat unfair to impose without further warning or clear statement.

PrawfsBlawg: Judicial supremacy and professional responsibility

by Howard Wasserman

The ethics complaint filed against Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton last summer will proceed to a State Bar investigation. (H/T: Josh Blackman) The complaint stems from a letter Paxton sent to county clerks in the wake of Obergefell, suggesting clerks and justices of the peace may have a religious exemption from issuing licenses or performing marriages to same-sex couples and that they may be able to assert those requests for exemption.

One of the challenges to the model of departmentalism I have been advocating (what Richmond's Kevin Walsh calls "judicial departmentalism") is the many doctrines that reinforce judicial supremacy. State bar regulations appear to be one of them, if this complaint against Paxton goes anywhere. The explicit problem, according to the complaint, is that Paxton ignored Obergefell and the (supposed) supremacy of SCOTUS's interpretation of the Constitution; his legal advice thereby ran afoul of several rules of professional responsibility. In fact, Paxton expressly acknowledged that any clerk or JOP who did this would almost certainly be sued, held liable in light of SCOTUS (and 5th Circuit) precedent, and subject to an injunction that would bind them. He simply recognized the need for that additional step. But that is not good enough; because it is "emphatically the province and duty," etc., an attorney, even one for the State, cannot give advice contradicting such judicial declarations. If this is what the regulations mean, they leave no room for departmentalism or for independent constitutional judgment in non-judicial actors; they instantiate judicial supremacy as the sole understanding for all attorneys, public or private.

On one hand, that could be permissible and appropriate. If a state legislature wants to establish judicial supremacy as the guiding principle for its attorneys, (so that, for example, the obligation to not advise a client to disobey a legal obligation includes obligations established in judicial decisions to which the client is not a party), it can do so. On the other hand, the automatic acceptance or presumption of judicial supremacy into the rule, without more, seems difficult to square. And somewhat unfair to impose without further warning or clear statement.

No comments:

Post a Comment